In Search of an Intuitive Interface?

Neontribe are big fans of open data, and last summer we got involved with a fascinating project using never-before-published data from the charitable sector. Our work made us revisit one of our fundamental assumptions about the goal of a user interface.

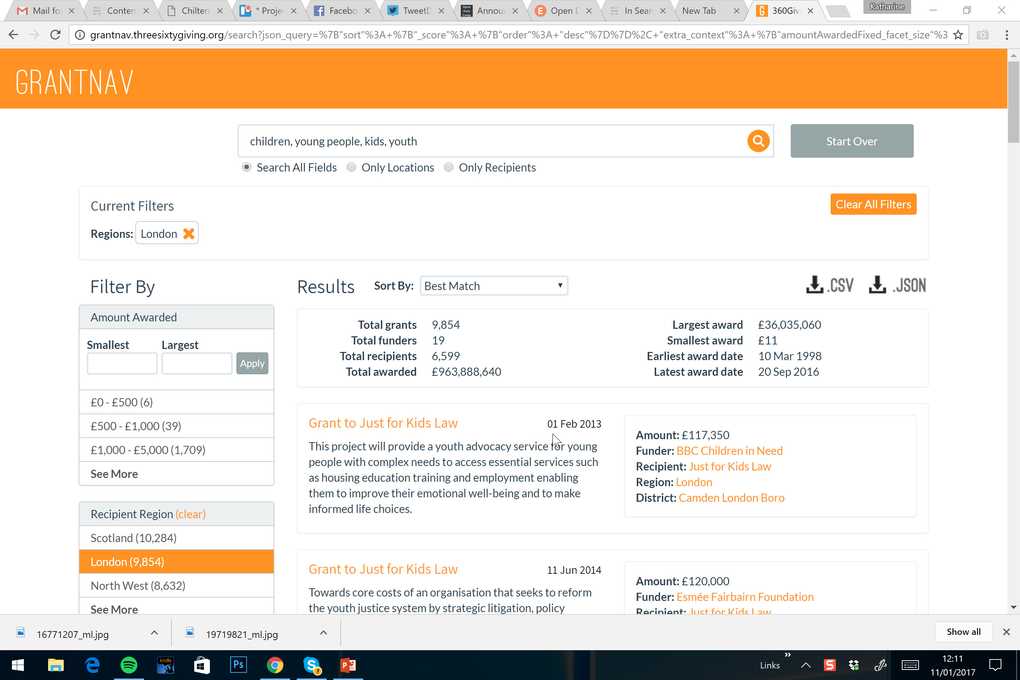

The opportunity came about thanks to a recommendation from a colleague at Open Data Services, Steven Flower. Steven and his team, well-known for their work on the OpenContracting Helpdesk and the International Aid Transparency Initiative, were working with 360Giving, a new initiative that supports organisations to publish their grants data and helps people to understand and use that data to improve decision making. 360Giving had already created a data standard and a data quality checking tool (CoVE) and engaged with some of the UK’s biggest and most influential donors including the Big Lottery Fund, BBC Children in Need and Comic Relief. Their next piece of development was to be GrantNav: an open access tool that allows anyone to explore the data published to the 360Giving Standard. When 360Giving approached us, the GrantNav project was ready for some user research.

The techniques we used would be familiar to anyone working in the field; starting with the creation of persona based on phone calls to some of the data publishers. These were then validated at a workshop which also explored story maps of journeys using the tool and the parallel journeys being taken in different types of charity offices across the sector. Once a beta of GrantNav was available, we also ran usability testing at various charity offices. These tests were flexible, carried out with both new and returning GrantNav users, and had as much value as a means of engaging with data publishers and discussing their overall interest in opening up their data as they did in exploring users' responses to the tool.

Together with 360Giving and Open Data Services, we started out with a goal common to every project team – let’s make a delightful, intuitive tool that everyone can use from the moment they land on its home page. However, our research caused us to collectively question not only how to achieve that, but whether, in this case, it should even be the development goal.

We thought that sharing some of the insights that led to this conclusion might be interesting to other teams doing similar work.

Our newest user researcher (me, Kat, writing this post) was gobsmacked when reporting back a no doubt common revelation about search in 2016. “Nobody uses quotation marks any more”. Never on their first search, and often not even after having exhausted every other option the interface seemed to offer to narrow their criteria down. This, combined with the common truth that many users only pay attention to a tiny proportion of what’s on the screen in front of them led to our first big discovery:

It was remarkably common when watching a user who was asked to search for an organisation’s funding history, to observe them type that organisation’s name into the search bar, hit go, scroll through their first few results, and ignore all the information about number, value, size of grants, recipients and funders shown above the search results. Believing they’d successfully isolated the data they wanted, they'd then and go right ahead and download a CSV file which additionally included over 5,000 different organisations that have received funds, each one sharing a part of the title of the organisation they'd originally searched for.

Why does this happen? We think it’s a function of an observation we don't think we're the first to make: that people want every search tool they use to “work like Google”. Unfortunately, in this particular case the way we use the internet, and particularly sites we often search or filter (eg jobs, holiday, house moving and shopping) teaches us expectations that are not always useful for data exploration tasks. Put more simply, the way we use Google and similar tools to find “one, or the best of something” does not help us when we are trying to find “all of something and nothing else” because we’ve trained our instincts for the former type of task.

It's true there are huge advantages to the fact that GrantNav mirrors the use of facets on familiar sites like Guardian Jobs or Rightmove. Those users with their CSVs of 5,000 organisations weren’t put off the tool. They were quick to explore other tasks, browse those “left hand lists”, find out what criteria they could view the data using, whether they are exclusive choices or whether they work together, and how they interact with the free text search on the data. So we didn’t think the right response to the stumbling blocks was to change the methodology from the ground up. After all, those users had only downloaded “one click too early”. Once shown their error, and how to follow a link directly to a recipient organisation’s funding history, they didn’t make the same mistake again.

Instead, we began to move towards a realisation. For GrantNav, we should not be overly concerned that the route to success to any individual task might not always be smooth. Sacrilegious in UX terms?

Maybe, but we are adamant it is right for this product and its users. GrantNav is not a tool with a single function that needs to ensure users complete an end to end journey. It’s an interface to a massive dataset, that has never been published to a single standard before, and which can be interrogated in almost endless ways. Attempts to simplify the tool would restrict this range of use.

More importantly, we rapidly became subscribers to the view that the idea that any of the websites and tools we use on a daily basis are instinctive is folly for most users. We don’t learn to use Facebook and Twitter to their fullest extent because their features are self-explanatory. Instead, we learn to use them because the internet provides countless “top tips” blogs that teach us new things to do, we learn to use them because a friend shows us how a certain feature works and we learn to use them because the cost of getting something wrong is small, and we find the process and results interesting enough to experiment.

The dataset behind GrantNav is complex. Every new publisher that gets involved is fascinated by the number of things it can do, and many are fascinated by the edges of what it cannot do, but can help with, by providing a CSV file which allows for further manipulation by sophisticated users. Our conclusion (alongside, of course, a bucket load of changes and additions that have helped Open Data Services prioritise their development tasks and streamlined many of the tool's functions) is that the real solution to making it easier for users to engage is not in additional development effort to simplify the interface.

Instead, we’re advocating for a digital engagement strategy that will provide the equivalent of those “top tips” articles that spring up organically for the sites with mass usage, and to build a community of users among charitable sector workers who can teach each other the different ways GrantNav can be used to work with them.

The most exciting thing about the journey has been just how quickly 360Giving has responded to that suggestion. This week, we have a meeting planned to explore how to develop that digital engagement, fired up about the possibilities inherent in combining user research work with engagement and partnership building, and integrating digital development right into the heart of 360Giving’s overall mission to support the charitable sector.